Art Work by Blacks Before They Could Paint Blacks

10 Groundbreaking African American Artists That Shaped History

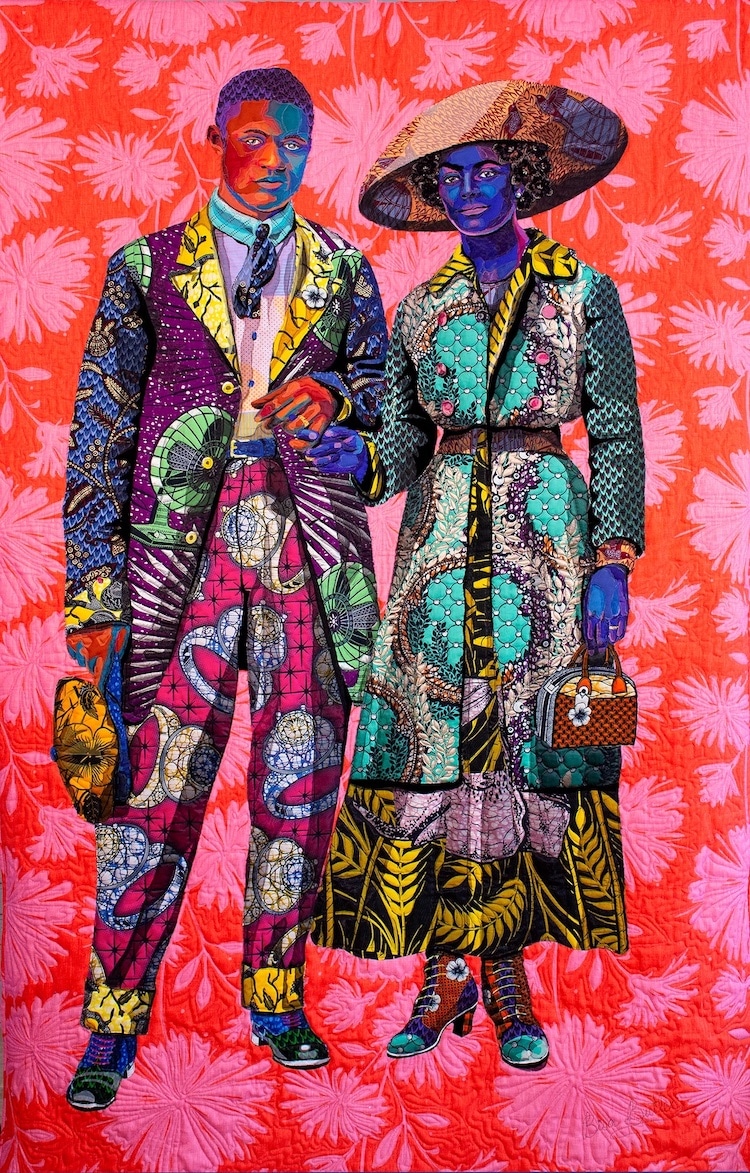

"Broom Jumpers," past Bisa Butler 2019 (quilted and appliquéd cotton wool, wool and chiffon | 58″ x 98″)

For centuries, African American artists have helped shape the visual culture of the United States. Oft channeling their familial backgrounds and personal experiences in their work, these creative figures have influenced and inspired much of American art's development.

Unfortunately, throughout history—both in the U.s.a. and beyond—artists of color take not aptly been recognized for their talents, achievements, and contributions. This has culminated in a popular history of art paved mostly by white artists. Fortunately, still, contemporary audiences are becoming increasingly interested in diversity in the arts, prompting museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions to shine an overdue spotlight on the piece of work of African American artists.

Groundbreaking African American Artists

"John Jacob Anderson and Sons, John and Edward" by Joshua Johnson. c. 1812 (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Joshua Johnson was a portrait painter living and working in 18th and 19th-century Baltimore. While niggling is known virtually his background (there are conflicting reports regarding whether or not he was enslaved), over 100 portraits are attributed to the artist. All of these pieces are rendered in a characteristically naive style and nigh share a distinctive composition: a sitter positioned in a three-quarter view, confronting a plain backdrop, and amid props ranging from fruit and flowers to parasols and riding crops.

Today, Johnson is celebrated as the earliest known African American who worked professionally as an artist, forging a path for numerous creatives to come.

Horace Pippin

Cocky-taught painter Horace Pippin one time said that his time served in WWI "brought out all the art in me." In fact, he took upwards art to rehabilitate his arm subsequently being shot in battle. In the 1930s, he began painting on stretched fabric and frequently revisited themes related to the war. As his career continued, he painted landscapes, every bit well equally political and biblical themes. His piece of work frequently touched on themes revolving around slavery and racial discrimination.

In 1947, he became the first African American artist to exist the discipline of a monograph. Today, his paintings can be found in individual and public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation, and the Phillips Collection.

Augusta Roughshod

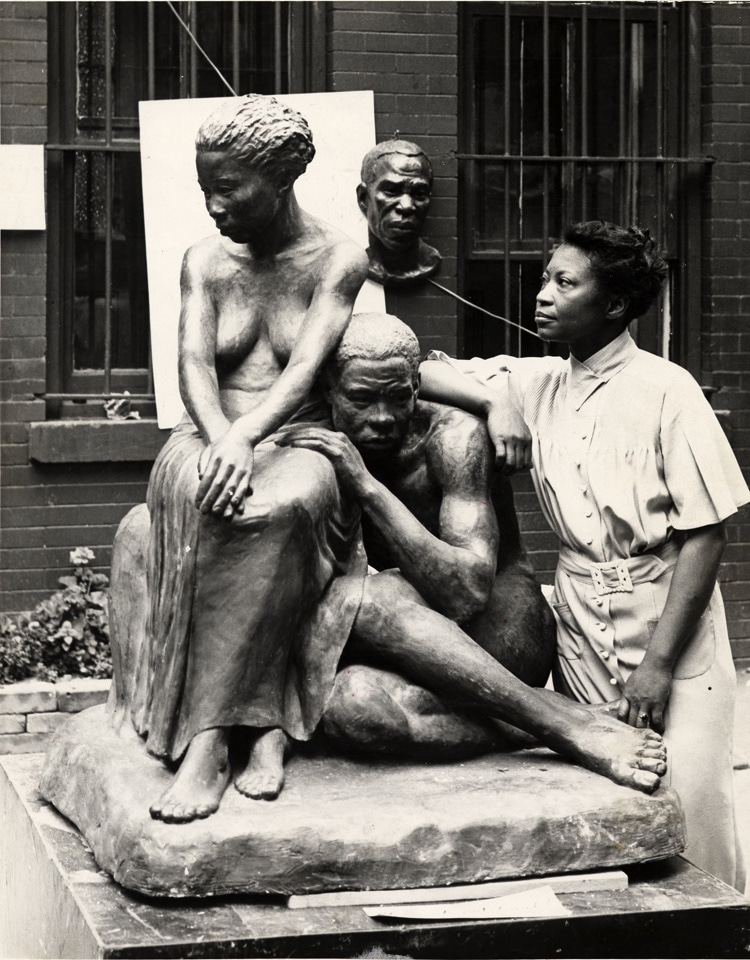

Augusta Brutal in 1938. Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia

In 1918, a groundbreaking motility emerged in New York City. Known today as the Harlem Renaissance, this "gold historic period" of art, literature, and music transformed the Harlem neighborhood into a cultural hub for African Americans, with Augusta Savage'due south many contributions at its core.

Brutal was a Florida-born sculptor. In 1921, she moved to New York City, where she attended The Cooper Union for the Advocacy of Science and Art, a scholarship-based schoolhouse. After earning her degree (an unabridged yr early), she was asked by the Harlem Library to create a bust of civil rights activist and writer W. Eastward. B. Du Bois—a piece that put her on the map.

Today, Roughshod's role in the Renaissance is mostly fastened to education and advocacy. In 1935, she co-founded the Harlem Artists Lodge, an organization that advised the neighborhood's African American artists; and, in 1937, she established the Harlem Community Fine art Center, where she led sculpting classes and helped launch the careers of African American artists, including Jacob Lawrence.

Romare Bearden

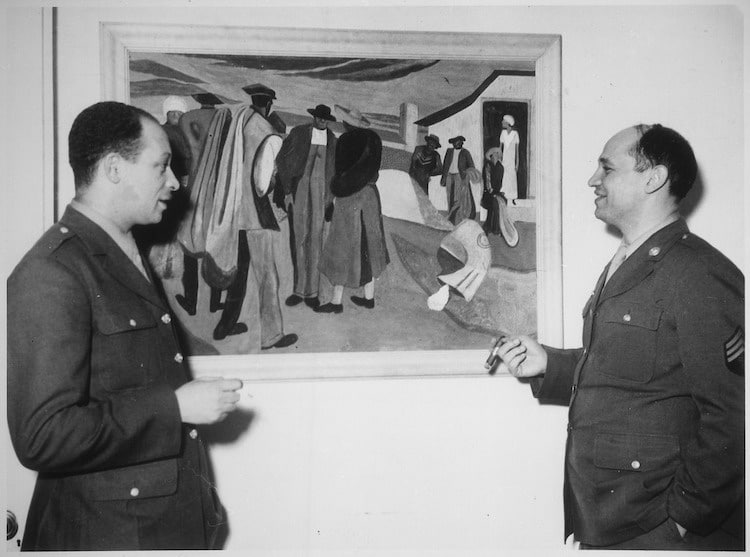

Romare Bearden (right) discussing his painting "Cotton Workers." 1944. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia, Public domain)

Born in 1911, Romare Bearden was a prolific creative who was not only a visual artist just too an author and songwriter. Throughout his long career, he experimented with different mediums, including oil paint and collage. His early work was influenced by Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, while he later evolved into a more abstract mode. In the 1960s, he started working with collages and focused his work on themes regarding cooperation and unity within the African American community.

Later on passing from complications with bone cancer in 1988,The New York Times called Bearden "ane of America'south pre-eminent artists."

Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence was born in New Bailiwick of jersey in 1918. At just 23 years old, he completed his Migration Series . This colorful collection of paintings tells the story of the Not bad Migration, a mass exodus of over 6 meg African Americans fleeing the segregated Southward to urbanized areas across the land.

Imagined as avant-garde shapes and rendered in bright tones, this work is celebrated as much for its bailiwick affair as its Harlem-inspired aesthetic. "Lawrence'due south work is a landmark in the history of modern art and a primal example of the way that history painting was radically reimagined in the modern era," the Museum of Modern Art explains.

After the success of this sixty-panel series, Lawrence continued to artistically document the African American feel in a number of projects. He besides taught at several universities and received numerous accolades and awards. In 1941, for example, he became the offset African American artist to have work featured in the Museum of Modern Fine art'southward permanent collection, and in 1990, he received the U.S. National Medal of Arts.

Aaron Douglas

Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1899, Aaron Douglas worked in a drinking glass factory and steel foundry in gild to earn coin for college. After graduating in 1922 with his caste in fine arts, he taught in the Kansas City, Missouri area before heeding the call of Johnson to head to New York City to exist function of the creative scene in Harlem.

Once in New York, Douglas studied painting with German language émigré artist Fritz Winold Reiss. He began to study African fine art equally a source of cultural identity while using what he learned near European modernism to create his own visual linguistic communication. His illustration and murals were centered around social problems—including race and segregation in the U.S.—presented in an abstruse, Cubist-deco style featuring semitransparent silhouetted figures that recalled African art.

Later on spending time in New York and Paris, Douglas accepted a full-time position in the art department at Fisk University in Nashville in 1944 and was there until he retired from education in 1966.

Jean-Michele Basquiat

New York City would continue to serve as a catalyst for Blackness artists for decades, with Jean-Michel Basquiat amid the Big Apple's most famous artists—and contemporary fine art's most universally recognized figures.

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn to a Puerto Rican female parent and a Haitian father in 1960. As a teenager, he helped pioneer and popularize street art, showtime with SAMO©, a tag serving as shorthand for "the same old sh-t," and eventually with his distinctive "craven-scratch" designs. Every bit a immature adult, he brought graffiti into the gallery, start in exclusive group shows and eventually as a sought-after solo artist.

Though he tragically died at just 27 years old, Basquiat's decade-long career led to a prodigious legacy. Today, he remains both a celebrated artistic and a cultural icon, recognized for his approach to themes like slavery and oppression. His works tin be found in peak museums and galleries around the globe, and they sell for tens of millions of dollars at auction.

Kara Walker

Like Lawrence and Basquiat, Kara Walker, a California-born artist, explores issues of race in her work. Rather than opt for a bright color palette, however, Walker often works in monochrome, whether crafting a faux-stone fountain, a saccharide sphynx, or, most prominently, her signature silhouettes.

Walker began creating silhouettes in 1994. Since then, she has continued to utilise these large-scale vignettes to creatively address the prevailing history of racism in the United States. Often, she imagines scenes ready in the Antebellum South—a fitting focal point considering the roots of the cut-paper craft. "I had a catharsis looking at early American varieties of silhouette cuttings," she said. "What I recognize, besides narrative and historicity and racism, was very physical displacement: the paradox of removing a form from a blank surface that in turn creates a black hole."

In addition to silhouette-making, Walker also dabbles in other mediums, creating everything from paintings and blithe works to shadow puppets and "magic-lantern" projections.

Kehinde Wiley

In 2017, Nigerian American portrait painter Kehinde Wiley made history when he became the first Black artist to pigment an official presidential portrait. Selected by President Barack Obama himself, Wiley was deputed to complete the painting for the National Portrait Gallery, whose collection of presidential portraits is amid its virtually of import holdings.

Since this major projection, Wiley has continued to reimagine traditional portraiture. He even challenged the expectations of equestrian painting with Rumors of War, a monumental sculpture that offers a gimmicky response to confederate statues. With this piece, Wiley rethinks the concept of a "hero"—and of American identity.

"Today," he said during the sculpture's unveiling in Times Square, "we say yes to something that looks like united states. Nosotros say yes to inclusivity. Nosotros say aye to broader notions of what information technology ways to exist an American."

Bisa Butler

Brooklyn-based artist Bisa Butler creates gimmicky quilts that are life-sized historical portraits of Black people whose stories may have been forgotten or completely disregarded in history. Each colorful moving picture utilizes fabric like a painter would paint to produce purple representations of each person.

Butler learned how to sew together by watching her female parent and grandmother. When she outset began creating her quilt art, she depicted her family. Now, she scours public databases for photographs that inspire her.

"My community has been marginalized for hundreds of years," she writes in her artist statement. "While we have been right beside our white counterparts experiencing and creating history, our contributions and perspectives have been ignored, unrecorded, and lost. It is merely a few years ago that it was best-selling that the White House was built by slaves. Right at that place in the seat of ability of our country African Americans were creating and contributing while their names were lost to history.

"My subjects are African Americans from ordinary walks of life who may have sat for a formal family portrait or may have been documented by a passing photographer," Butler explains. "Like the builders of the White Firm, they accept no names or captions to tell united states of america who they were."

Hear Bisa speak about her work in-depth on the My Mod Met Superlative Artist podcast.

This commodity has been edited and updated.

Related Manufactures:

Colorful Quilts Crafted from African Fabrics Tell Stories of Creative person's Ancestral Homeland

New York Subway Murals Celebrate Influential Icons from Bronx History

five-Yr-Onetime Daughter Recreates Photos of Inspiring Women Every Day of Black History Month

Source: https://mymodernmet.com/african-american-artists/

0 Response to "Art Work by Blacks Before They Could Paint Blacks"

Post a Comment